Slaying Dragons

Tabletop RPG

Published by Bläckfisk Publishing

My Role

Game designer

Team Size

1 during development

3 during launch

Time Spent

1 year

Year

Slaying Dragons is a tabletop role-playing game about metaphorically slaying your dragon.

In this game there is no doubt whether or not you’ll succeed; you will. You will make your way to the beast’s lair. You will find the hidden secrets within. And you will finally slay the dragon.

The question is what you’ll learn about yourselves in the process, and what price you will pay for your growth.

Video Coverage

First Impressions by Mindy Bräd- och Rollspelspodd (swedish)

2021

How it plays

Play is divided into two phases: adventuring and making camp.

In the adventuring phase players take turns narrating a story in an episodic style inspired by J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit. Each player presents obstacles for the others to overcome, and dice and prompts are used to inject emotional content into the plot in an unpredictable fashion.

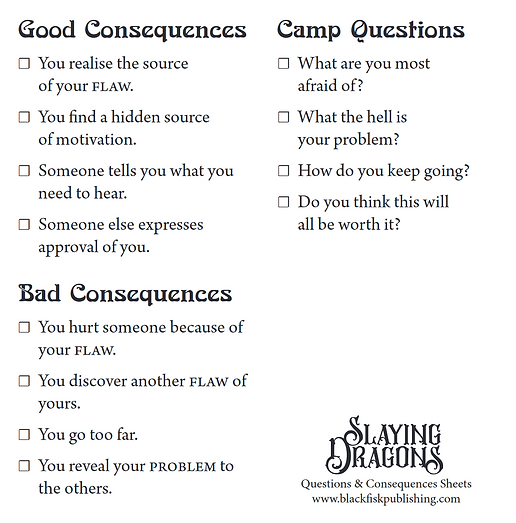

After adventuring, making camp takes over. Here the players play out a scene where their heroes are making camp after a long and hard day. To drive the tension in camp scenes the players are given questions which their characters will ask each other.

The cycle of Adventuring and Camp phase are repeated three times, corresponding to a 3 act structure. Each new iteration has new prompts and questions to guide the players towards the desired intensity at that point in the story.

Process

Slaying Dragons began as a project from a dare that ended up showing more promise than expected. The initial concept that sparked development was of building a story around always succeeding, but at what cost.

My first playable prototype contained the adventuring phase only and focused on generating narrative side-effects through dice. This system was so successful as to remain mostly unchanged through the entire process.

Since the game requires players to physically mark options they have chosen on paper I had raw data on the popularity of individual prompts. Through computer simulations I also had a clear image of expected act and game length as well as respective variance.

These metrics together with qualitative assessment and feedback from players formed the basis of my design decisions.

A major issue facing this project was game length. On average a session of the full prototype took between 25-50% longer than the target time of 4 hours. This poses a large threat to a game in a genre where 3 to 4 hours play time is standard.

Three approaches were explored to address this: turn order adjustments, probability adjustments of good vs bad consequences, and pause and resume routines. The most significant of these proved to be turn order.

Turn order in Slaying Dragons during adventuring phases is complex. Three things must happen per player turn:

-

Another player narrates the obstacle

-

The player rolls a die and narrates the outcome

-

The same player then journals their experience

To minimize the amount of time this takes, we want as much concurrent behavior as possible. To achieve this, I went for a turn order where the journaling player is never needed for the next turn. In graph form:

To make this process simple to communicate to players I introduced a turn order marker, and defined the "current player" as the player narrating the obstacle. With these changes, the turn order simplifies to the graph below, without losing concurrency advantages.

.png)

After failing to fully address the game length concerns, development went into hiatus for almost a year. I resumed working on the project after my publisher expressed interest in the game.

In order to publish the game on time, a compromise for the game length was found. By providing instructions for how to pause the game and resume it at a later date, players who did not wish to spend 5 hours in one sitting could still play the game.

What I learned

Slaying Dragons was the first game I shipped with a compromise built into the product. To get this product out the door, I had to learn to let go of a game I cherished before I felt ready. I am very glad I did.

This game also showed me what I can do with rapid iteration and heavy use of quantifiable data. Slaying Dragons set a new standard for me in how much math and statistics I put into a game. These days I always keep a number-crunching library at hand for when the next project comes.